After more than two weeks in Iceland, Meyer brothers’s second trip ended on Thursday, March 10. What an adventure! This island of about 360,000 people never ceased to amaze us with its entrepreneurial innovations, culture, vibrancy, climate and beauty.

By meeting with several local enterprises and pioneers in the field of managerial innovation in Iceland, we tried to understand the culture of the country and its impact on management practices.

Góð lesning ! (Enjoy your reading)

Several cultural aspects impressed them:

– Icelanders’ agility and adaptability to the unexpected (linked to a changing and extreme climate): Icelanders are used to extreme and uncertain weather conditions (in Reykjavik it can be raining, snowing, hailing, sunny and cloudy on the same day, while 100 km away a volcano is erupting), and this seems to have consequences on their behavior in business! Pétur Arasson, pioneer of Icelandic managerial innovation and CEO of the Manino enterprise tells us, “I hate planning.” The same goes for our guide when we visited one of the caves of Europe’s largest glacier, Vatnajökull: “In 40 years, I have never planned a weekend in Iceland in advance.”

– This agility goes hand in hand with their culture of action, of “do it” coupled with a relentless positivity: Pétur explains that Icelanders like to believe that “No matter how it is done, it will work.” He cites the example of Iceland’s first participation in the 2016 European Soccer Championship. The national team had surprised the world by reaching the quarterfinals and knocking out the English team in their first participation in a European Soccer Championship.

– Their low sense of hierarchy, similar to Norway, or their serenity about the future: Eldar from Crowd Control Productions explains that the enterprise organization is still hierarchical (manager, N+1, N+2, board of directors, etc.), but that this is not really noticeable. Everyone is accessible, even in large structures. Pétur from the Manino enterprise says that Icelanders do not really appreciate hierarchy and authority. He thinks this may be partly because the Icelandic army, which in people’s minds is the ultimate symbol of a well-defined hierarchical organization, is almost non-existent.

Another issue was of particular concern during our interviews: gender equality, which is of paramount importance to Icelanders.

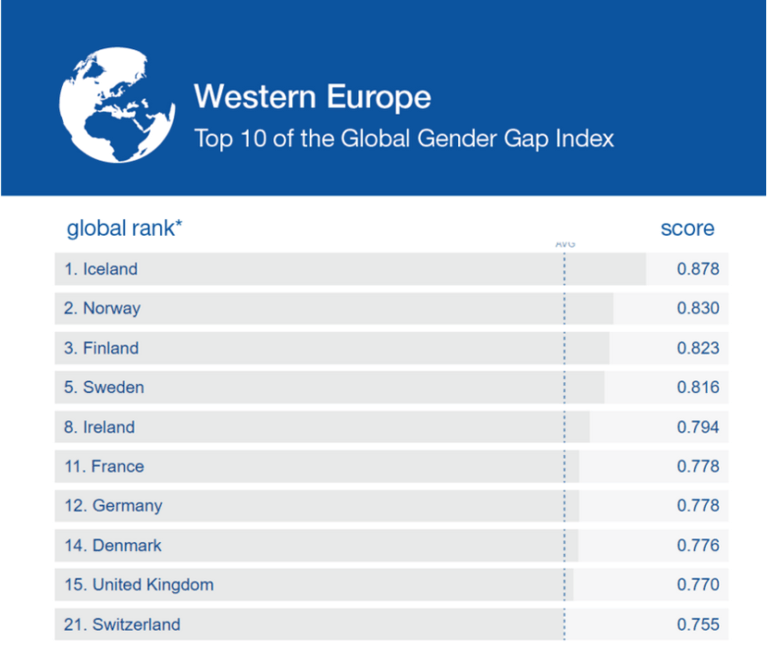

As Iceland tops the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index, we wondered during our time there how the country has become a pioneer in the fight against gender inequality.

Global Gender Gap Report 2017, World Economic Forum

In this public article, Clément and Romain give you some answers through the prism of education, policy and legislation, and our interviews with Icelandic enterprises.

Gender equality is a priority issue in Iceland. The results are very present and we could observe on the ground how important the issue is in the eyes of the Icelanders we met.

– According to the World Economic Forum, Iceland has eliminated nearly 90% of the gender gap.

– For the past 9 years, Iceland has topped the Gender Gap Index, a ranking compiled by the World Economic Forum based on the degree of equality and distribution of opportunities between women and men.

– The employment rate of Icelandic women is very high (83% in 2019, according to Eurostat, compared to 66.8% in the Eurozone). They are better represented in parliament, ministries and administrations than in most European countries.

– According to the latest Eurostat data, the average hourly pay gap between men and women was 13.9% in 2019, compared to 15% in the Eurozone and 16.5% in France. For comparable jobs and qualifications, the gap drops to 4.3%, down from 6.2% in 2010, according to Statistics Iceland.

– Icelanders are leading the way on these issues and are trying to involve other countries in this fight: Iceland is behind the International Equal Pay Day. This event was launched in 2019 under the auspices of the International Coalition for Equal Pay. Its goal is to deepen concrete action to close the gender pay gap by 2030 on all continents. This year, the focus was on efforts following the Covid-19, as the pandemic has further widened the gender pay gap, which is estimated to have increased to an average of 20% globally in 2019.

In our professional and casual meetings with Icelanders, we realized the importance of the issue. In fact, 70% of the professionals we met were men, and without exception, all mentioned the need to reduce gender inequalities without us even asking the question. While the issue of trust came up regularly in our conversations in Norway, it was the issue of gender equality that came up most spontaneously in Iceland.

How can we explain the importance of the issue in Iceland and the country’s excellent results in reducing gender inequality?

Iceland has long been a pioneer in the fight against gender inequality.

Social achievements in the area of equal opportunity are often the result of struggles, and Icelandic women have excelled in this field on many occasions.

On October 24, 1975, when Icelandic women were earning 60% less than men, 90% of Icelandic women decided to walk off their jobs to defend their rights, demand a pay raise, and advocate for greater recognition of their role in society. This demonstration was also an opportunity for women to show that their activity was necessary for the functioning of the country. This date marked the beginning of an emancipation movement for Icelandic women.

This movement led to the creation of the Women’s Alliance in 1983, a political party that allowed women to enter Parliament. Five years after this historic protest, Vigdís Finnbogadóttir of Iceland became the first woman in the world to be elected president by direct universal suffrage.

In the September 2021 parliamentary elections, 47.6% of seats were held by women, a record in European political history.

Pétur Arason states during one of our conversations, “All of this must begin with education”.

To prove to us that Iceland is addressing the issue of gender equality from the youngest age, he recommends a visit to the “Hjalli Model School”, a preschool with a unique teaching method founded in 1989 by Margrét Pála Ólafsdóttir.

One of the most memorable moments of our Odyssey.

The Hjalli schools are well known in Iceland (the waiting lists for enrollment are endless). Today they welcome 2000 children and employ 500 people.

Margrét’s greatest mission is to use the Hjalli model to offer girls and boys the same educational experiences, the same challenges, without gender discrimination.

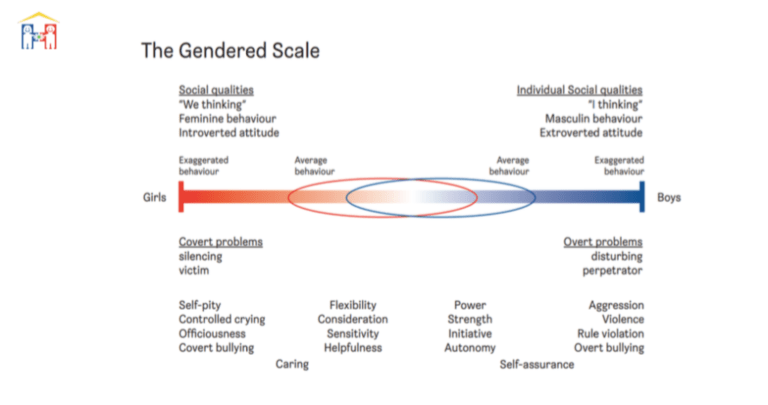

Her purpose is to guide everyone to overcome the traditional behaviors attributed to boys (strong, autonomous, and insensitive) and girls (sensitive, empathetic, silent) that she has observed in her previous experiences in elementary schools and whose stereotypes are fed by educational teams that often lack awareness of this issue. In particular, she points to the way girls are addressed (often as a group), “you are beautiful and behave better than boys, etc.” and boys (individual communication, “you are strong, you are turbulent), but also to the attention given to both genders. According to Margrét, the fact that boys can demand more attention from the educational institution (behavioral aspect) can lead to girls going through an entire educational system and finding that they are less important than boys.

In her view, it is necessary to compensate for the stereotypes conveyed by society that all children encounter on a daily basis.

To achieve this, the Hjalli model relies on single-gender classes to give equal attention to all, even though it is obvious to Margrét that mixed activities must take place during the day.

Thus, girls and boys must meet for an hour each day to develop complicity, respect, and have fun.

Here are some other exercises that are done daily in the school that surprised us:

– Tonic exercise every morning for the girls during reunion while the boys practice meditation.

– The girls practice shouting “we are strong”, “we can achieve anything we want”, while the boys compliment each other in a circle. (We participated in this compliment session, an unforgettable moment).

– Moving around the school, the boys are always in pairs, holding hands, while the girls have to walk the hallways alone.

– Walking barefoot in the snow and on small stones for the girls to build confidence!

In her view, it is necessary to compensate for the stereotypes conveyed by society that all children encounter on a daily basis.

To achieve this, the Hjalli model relies on single-gender classes to give equal attention to all, even though it is obvious to Margrét that mixed activities must take place during the day.

Thus, girls and boys must meet for an hour each day to develop complicity, respect, and have fun.

Here are some other exercises that are done daily in the school that surprised us:

– Tonic exercise every morning for the girls during reunion while the boys practice meditation.

– The girls practice shouting “we are strong”, “we can achieve anything we want”, while the boys compliment each other in a circle. (We participated in this compliment session, an unforgettable moment).

– Moving around the school, the boys are always in pairs, holding hands, while the girls have to walk the hallways alone.

– Walking barefoot in the snow and on small stones for the girls to build confidence!

In Margrét’s view, boys must also reject stereotypes. There is room for heckling, but they also learn to be loving. For the director: “Women and young girls should not have a monopoly on feelings”.

The Hjalli Model Gender Scale

A profound work carried out from a young age, helping to build a solid base in the fight against gender inequality.

Simply put, enterprises must prove that men and women in the same position and with the same skills receive equal pay.

The law is punitive, as enterprises that do not comply can be fined up to ISK 50,000 (€ 330) per day.

The island stands out on the subject in the professional world with the so-called “Reverse Burden of Proof” law. In effect, since January 1, 2018, Iceland has become the first country in the world where pay parity is mandatory and controlled.

Moreover, an independent body verifies that these criteria are met according to a series of indicators and issues a certification to be renewed every 3 years.

CCP enterprise certification to ensure pay parity for the same position

We were able to observe the application of this law during our visit to the enterprise CCP Games. CCP employs more than 250 people and has received this certification.

This also applies to the state-owned enterprise Central Public Procurement, which had to reduce unjustified gender pay gaps from 5% to 0%.

Lastly, like the Norwegian parental leave we mentioned in our first public article, the Icelandic parental leave is extensive. It lasts nine months. Of these nine months, one third is reserved for the mother, one third for the father, and one third can be shared between the two parents. As a result, 90% of fathers take part of the leave.

Iceland impresses with its willingness to reduce gender inequalities.

However, there are some limitations.

Let us take the example of the so-called “Reverse Burden of Proof” law. One of the risks of this law is that it restricts salaries and hiring. Indeed, increasing the salary of one employee leads to the need to increase all other employees or to justify the difference in salary. In a country like France (with more inhabitants and enterprises), the negative consequences could be even more serious and the administrative slowness, especially for large enterprises, even greater. The labor market is also evolving. A developer can have an average salary of 45,000 euros one year and 50,000 euros another year if there is a shortage of skilled workers. Hiring a new developer would force the organization to raise the rest of the staff, which can easily discourage some enterprises from hiring.

Another problem is still very present in Iceland: low pay in professions dominated by women. For example, paramedical professions in Iceland are predominantly female. The appreciation of certain professions that are mainly performed by women may be lower than that of certain professions that are more masculine (especially in industry).

Consequently, as we noted in the introduction, the average hourly wage gap for the same occupations is relatively small, but the gender wage gap is bigger on average.

Although there is still a long way to go to fully reduce gender inequalities in Iceland, Icelanders remain pioneers on this issue. In addition to the numbers, it is the Icelandic mentality and awareness of this issue that impressed us the most.

– Article from the World Economic Forum that details Iceland’s positive score in the fight against gender inequality: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/11/why-iceland-ranks-first-gender-equality/

– Another interesting article from Alternatives Économiques that questions the law of the Reverse Burden of Proof: https://www.alternatives-economiques.fr/inegalites-salariales-faut-imiter-lislande/00082588

– Articles to understand the topic more precisely:

https://www.la-croix.com/Monde/LIslande-pointe-legalite-entre-femmes-hommes-2021-09-28-1201177704

We hope you enjoyed this article!

Clément & Romain Meyer from l’Odyssée Managériale

French version: https://odysseemanageriale.com/2022/03/30/etape-2-islande-%f0%9f%87%ae%f0%9f%87%b8/

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |